6 Land Use Regulations in Northern Virginia: A National Zoning Atlas

By Eli Kahn, Andrew Crouch, and Emily Hamilton1

Originally published at Mercatus.

6.1 Introduction

In recent years, policymakers have sought solutions to the housing shortages that plague their constituents with increasing urgency. Following decades of research and increasing activist pressure to reduce restrictions on homebuilding, these policymakers and scholars are looking critically at zoning regulations and local rules that shape the type and quantity of housing allowed to be built. Local policymakers largely determine their own zoning rules and permit-approval processes, and learning how land use is regulated across locales requires consulting zoning ordinances in tens of thousands of jurisdictions in the United States.

The lack of data on zoning regulations in various local jurisdictions where they are enacted has previously inhibited research on how these rules specifically affect housing construction and prices. The National Zoning Atlas (NZA) addresses the limited information on zoning rules across the country by compiling data on rules that constrain housing construction. Researchers at the NZA along with local teams across the country have been contributing to the atlas since 2020, with complete data for nearly 3,000 jurisdictions so far. Over the past year, our team added Northern Virginia to the NZA database, creating an in-depth picture of the current regulation of housing in one of the nation’s most prosperous regions.

In this policy brief, we explain the value of collecting data on zoning and the NZA methodology, we detail results from our analysis of regulations in Northern Virginia, and we provide context for our findings.

6.2 Measuring Zoning

The NZA project is an effort to provide granular data on land use regulations for each zone in the country where housing is allowed. After identifying the zoning districts within a jurisdiction, analysts log whether the districts are primarily residential, mixed with residential (namely, mixed use including residential), or nonresidential. Primarily residential zones allow housing and may permit limited other uses, such as schools, churches, and utilities. Mixed with residential zones generally allow housing and retail or office development. Nonresidential zones include industrial zones, which may have health and safety reasons for separation from housing, along with commercial zones where housing is not permitted, government zones, and land zoned for open space.

The atlas also provides detail on whether rules allow for one, two, three, or four or more housing units on a lot and how the size and shape of those buildings are restricted. This requires analysts to investigate questions such as these: Are two-family structures allowed to be built at all? Are they only allowed after a public hearing? How much land area do they require?

For zones that allow residential construction, the atlas includes data on the following regulations:

Minimum lot size

Front setback

Side setback

Rear setback

Maximum lot coverage

Minimum parking spaces

Maximum stories

Maximum height

Maximum floor-to-area ratio

Minimum unit size

For two-, three-, and four-plus-family housing, the following regulations are added:

Maximum density

Connection to utilities and/or transit (3 and 4+ family only)

Maximum bedrooms (3 and 4+ family only)

Maximum units per building (4+ family only)

The atlas also includes regulations on accessory dwelling units (ADUs), affordable housing, and planned residential developments. This rich data collection provides value for a range of audiences. Although not all atlas teams have made their complete datasets public, many have. The full dataset on zoning in Virginia will be available on the NZA website, with regional teams’ data being added as they are completed.2 These data will provide researchers with the tools to estimate answers to questions such as, “What combination of rules makes duplex construction feasible?” or “To what extent do builders choose to provide off-street parking when zoning rules don’t require it?”

Currently, the Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index (WRLURI)3 developed in 2006 and updated in 2018, is one of the most widely used tools for comparing zoning regulations across the United States. The index is derived from survey data collected from a municipal employee or an elected official in US localities. The 2018 survey received partial or full responses in 2,844 localities.

WRLURI questions on land use policy fit into three buckets: (1) the permitting processes, (2) the rules limiting housing construction (i.e., minimum lot size requirements), and (3) the time the permitting process requires for different types of residential development. The WRLURI is the first tool to have provided researchers with the ability to compare the burden of zoning rules across jurisdictions and, together, the 2006 and 2018 data are the first measurement of the change in land use regulations across the country over time. Some studies use more detailed data on land use restrictions, but they tend to cover small geographical areas.4

Research using the WRLURI and other proxies for the burden of land use regulations across regions has shown that these rules have significant effects on housing markets and the broader economy. More restrictive land use regulations are associated with higher housing costs, more residential segregation, reduced income mobility, and even lower fertility rates.5

Although a growing body of research indicates that local zoning regulations have important effects on housing affordability and economic opportunity, researchers have not had precise data on local zoning rules across the country to study the effects of specific land use regulations. For example, the WRLURI provides data on whether a locality has any large lot zoning, but it lacks data on specific lot size requirements across zones.

The atlas also creates new opportunities for apples-to-apples comparisons of zoning in localities across the United States, potentially pointing policymakers to zoning reform opportunities that are well suited to their jurisdictions. Advocates can use the data to see specifically how reform proposals will change what can be built in their states or localities. In the following section, we describe the NZA findings in Northern Virginia for major categories of residential land use restrictions.

6.3 Residential Land Use Rules in Northern Virginia

We have gathered zoning data for the 23 jurisdictions with a total of 534 zones in the Northern Virginia region (Figure 6.1).6 The region includes four counties (Arlington, Fairfax, Loudoun, and Prince William) and five independent cities (Alexandria, Falls Church, Fairfax City, Manassas, and Manassas Park). Across all of Northern Virginia, 84 percent of developable land is categorized as primarily residential under the NZA’s typology, encompassing residential districts and agricultural districts, which generally permit housing construction by right, but excluding most mixed-use districts (Figure 6.2). The percentage of land zoned for primarily residential uses varies widely by locality, with Manassas Park being the lowest (26.4 percent) and Hillsboro being the highest (98.7 percent). Eight percent of the land in Northern Virginia is classified mixed with residential, with the remaining 8 percent classified as nonresidential.

Single-family detached houses, the most expensive type of housing, are the only form of housing allowed in many primarily residential districts. In general, once a neighborhood is developed with detached single-family houses, zoning locks this development pattern in place, preventing the neighborhood from accommodating more people even if demand for housing and house prices increase markedly.

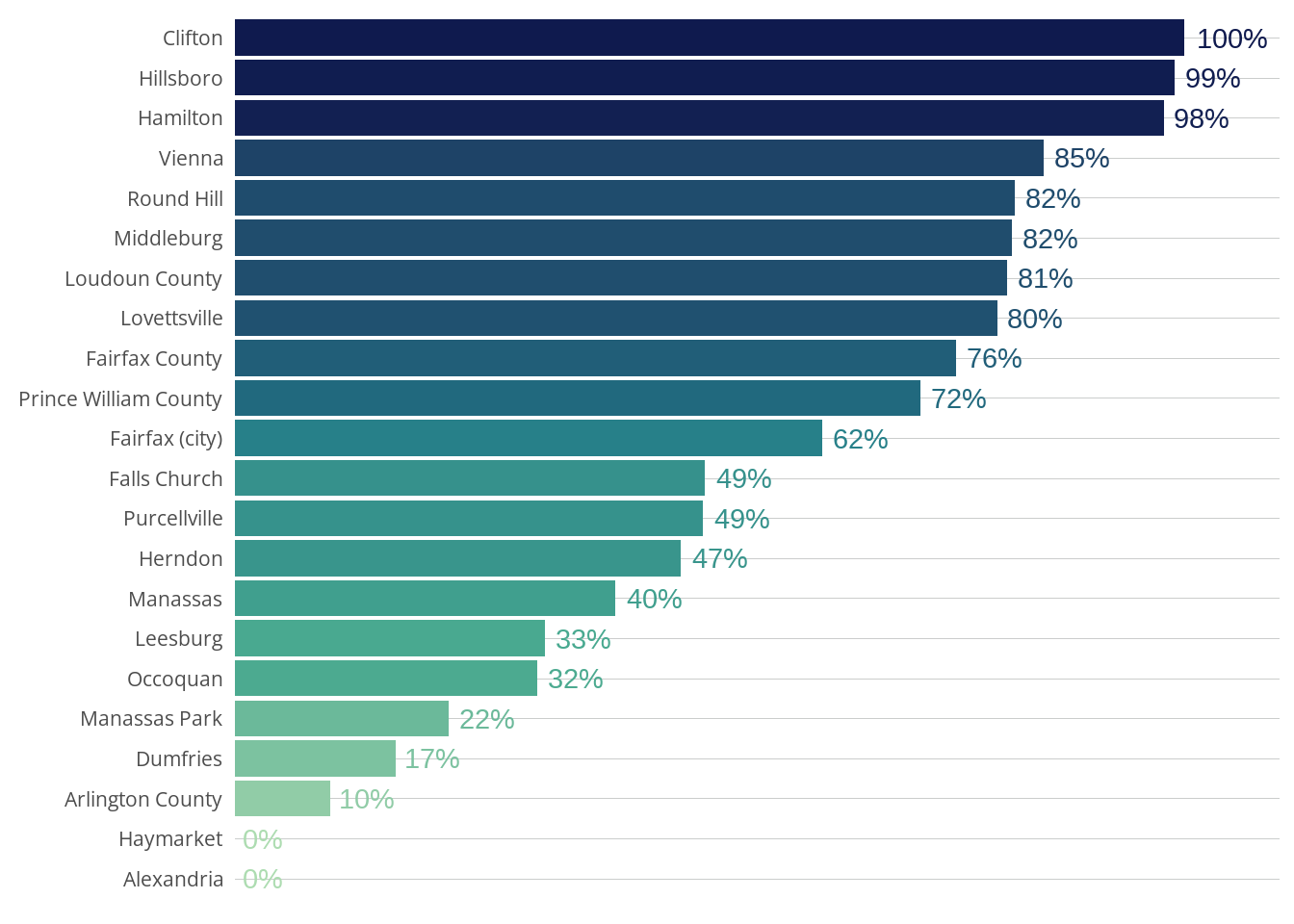

The share of land zoned for exclusively single-family houses similarly varies across jurisdictions (Figure 6.3). The small towns of Clifton and Hillsboro are zoned almost entirely for single-family detached housing, whereas none of the primarily residential land in Arlington or Alexandria is restricted to single-family detached homes any longer, following 2023 reforms in both localities. Many commercial districts in Arlington, by contrast, still permit single-family detached homes by right while requiring a public hearing process for other residential uses; this is unaffected by the 2023 ordinance, which specifically revised the regulations in what had been single-family-home residential districts. However, the County Board approves extensive multifamily housing in these commercial zones through its special exemption process.

Although single-family zoning as a category rightly receives much focus from advocates and policymakers, the cost and density of single-family development varies widely across different single-family zones. Minimum lot size regulations determine how much land is required for each single-family house. The requirements for lot size in a given zone often vary depending on whether sewer and water infrastructure or other public services are available. To compare minimum lot size requirements across jurisdictions, we calculate each locality’s average minimum lot size required for land on which only detached single-family housing is allowed by right, assuming that any infrastructure needed for the smallest required lot size is already in place. Of the 20 jurisdictions in Northern Virginia, 13 have an average of less than one acre (Figure 6.4). Lovettsville has the smallest average minimum lot size of 0.16 acres, whereas Round Hill has by far the largest with 5.24 acres. Nationally, the median new-construction house has a lot size of about 0.18 acres.7

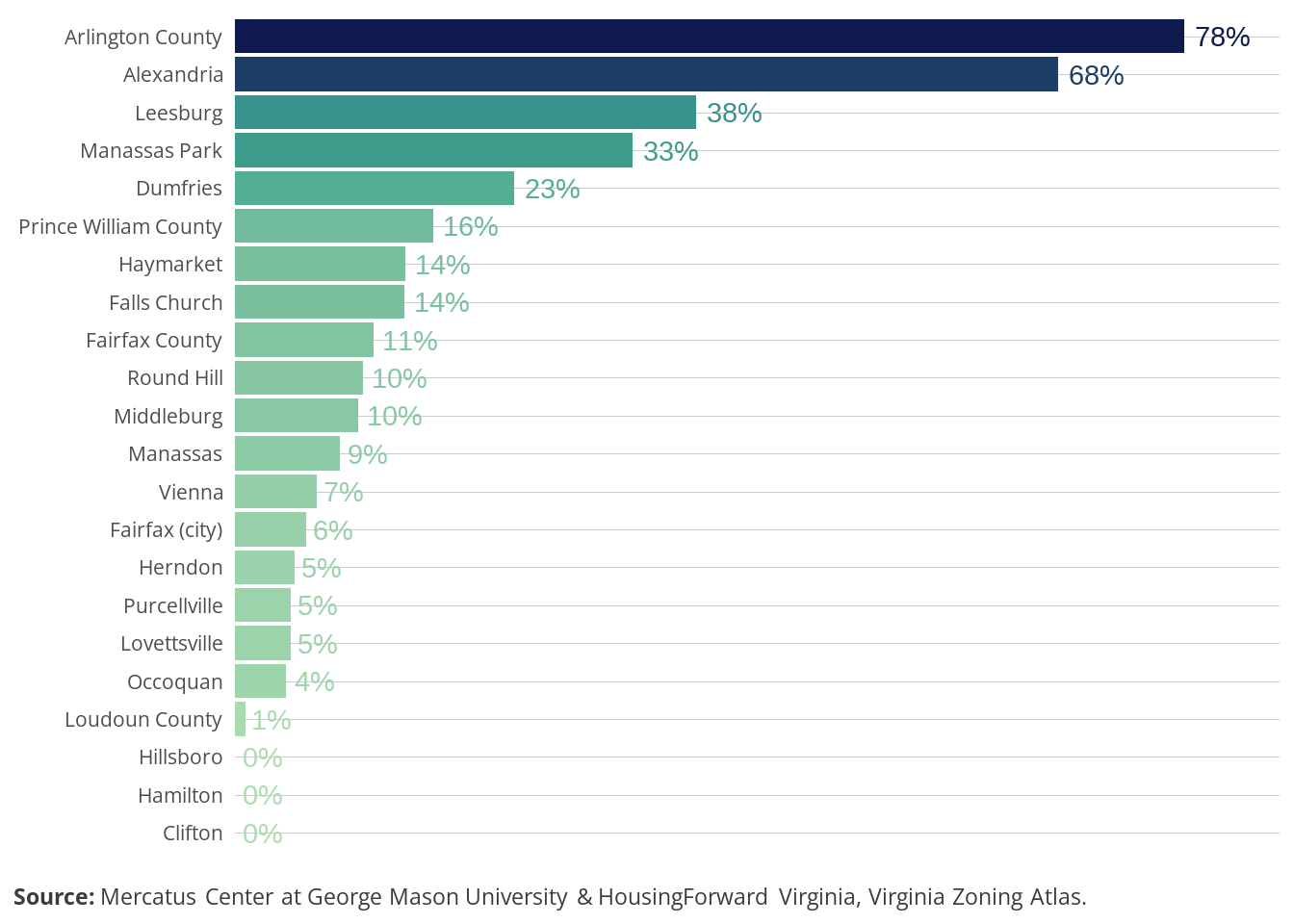

Land on which buildings with four or more units are allowed is just 9.5 percent of land overall (Figure 6.5). In most Northern Virginia jurisdictions, multifamily construction is primarily confined to downtown or other commercial areas. This situation also varies significantly across jurisdictions, with 73 percent of Arlington allowing for these buildings but none of Clifton, Hamilton, or Hillsboro allowing for them.

Accessory dwelling units have emerged as one of the most popular tools for fighting the housing shortage. ADUs are secondary housing units on a piece of land zoned for another use. They are most commonly built on single-family lots as basement apartments, backyard cottages, or converted garages. ADUs offer a means to increase the number of housing units available for occupancy without dramatically changing the built environment (or in some cases, without changing the built environment at all). On 65 percent of the developable land in Northern Virginia, ADUs are allowed by right, including on 77 percent of land zoned exclusively for single-family detached housing (Figure 6.6).

Reading layer `nova_region' from data source

`C:\Users\ericv\Desktop\github\virginiazoningatlas\data\nova\geo\nova_region.geojson'

using driver `GeoJSON'

Simple feature collection with 23 features and 5 fields

Geometry type: MULTIPOLYGON

Dimension: XY

Bounding box: xmin: -77.9622 ymin: 38.50079 xmax: -77.03217 ymax: 39.3246

Geodetic CRS: WGS 84